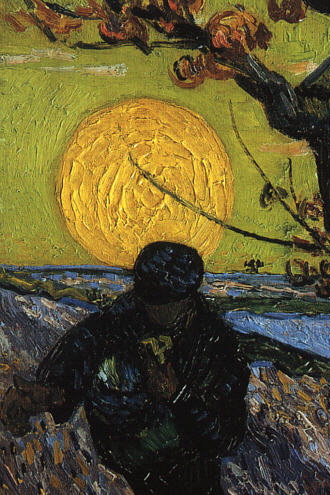

Bartolome Murillo

In Eastern Christianity

In the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Traditions, the Ever-Virgin Mary, the Theotokos, died, after having lived a holy life. Eastern Christians do not believe in the immaculate conception, on the contrary believing that she was the best example of a human lifestyle. Eleven of the apostles were present and conducted the funeral. St Thomas was delayed and arrived a few days later. Wanting to venerate the body, the tomb was opened for St Thomas. It was revealed that the body of the Theotokos was gone. It was their conclusion that she had been taken, body and soul into heaven. While every Orthodox Christian believes this to be true, the Orthodox have never formally made it a doctrine. It remains a holy mystery. The Eastern Orthodox celebrate this event on the 15th of August. The Oriental Orthodox celebrate it on August 22. The feast day of the Dormition (“falling asleep”) of the Theotokos is preceded by a two week fasting period.

[edit] Anglican Recognition of the Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary’s special position within God’s purpose of salvation as “God bearer” (theotokos) is recognised in a number of ways by some Anglican Christians. The Church affirms in the historic creeds that Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary, and celebrates the feast days of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. This feast is called in older prayer books the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 2 February. The Annunciation of our Lord to the Blessed Virgin on March 25 was from before the time of Saint Bede until the 18th century New Year’s Day in England. The Annunciation is called the “Annuncation of our Lady” in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. Anglicans also celebrate in the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin on May 31, though in some provinces the traditional date of July 2 is kept. The feast of the St. Mary the Virgin is observed on the traditional day of the Assumption, August 15. The Nativity of the Blessed Virgin is kept on September 8.

The Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary is kept in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, on December 8. In certain Anglo-Catholic parishes this feast is called the Immaculate Conception. Again, the Assumption of Mary is believed in by most Anglo-Catholics, but is in considered a pious opinion by moderate Anglicans. Protestant minded Anglicans reject the celebration of these feasts.

Prayer to and with the Blessed Virgin Mary varies according to churchmanship. Low Church Anglicans rarely invoke the Blessed Virgin except in certain hymns, such as the second stanza of Ye Watchers and Ye Holy Ones. Anglo-Catholics, however, frequently pray the rosary, the Angelus, Regina Caeli, and other litanies and anthems of Our Lady. The Anglican Society of Mary maintains chapters in many countries. The purpose of the society is to foster devotion to Mary among Anglicans.

[edit] Christian Veneration of Mary

The oldest-known image of Mary depicts her nursing the Infant Jesus. 2nd century, Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome.

Catholic, Orthodox and some Anglican Christians venerate Mary, as do the non-Chalcedonian or Oriental Orthodox, a communion of churches that has been traditionally deemed monophysite (such as the Coptic Orthodox Church of Egypt and the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church). This veneration especially takes the form of prayer for intercession with her Son, Jesus Christ. Additionally it includes composing poems and songs in Mary’s honor, painting icons or carving statues of her, and conferring titles on Mary that reflect her position among the saints. She is also one of the most highly venerated saints in both the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches; several major feast days are devoted to her each year. (See Liturgical year.) Protestants have generally paid only a small amount of reverence to the Blessed Virgin compared to their Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox counterparts, often arguing that if too much attention is focused on Mary, there is a danger of detracting from the worship due to God alone. By contrast, certain documents of the Second Vatican Council, such as chapter VIII of the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium [2] describe Mary as higher than all other created beings, even angels: “she far surpasses all creatures, both in heaven and on earth”; but still in the final analysis, a created being, solely human – not divine – in her nature. On this showing, Catholic traditionalists would argue that there is no conflation [3] of the human and divine levels in their veneration of Mary.

Moses and the Burning Bush: Nicolas Froment, 1476: a major commission from René I of Naples for the cathedral at Aix-en-Provence shows the apparition in the Burning Bush as the Blessed Virgin in a bower of flaming roses.

The major origin and impetus of veneration of Mary comes from the Christological controversies of the early church – many debates denying in some way the divinity or humanity of Jesus Christ. So not only would one side affirm that Jesus was indeed God, but would assert the conclusion that Mary was “Mother of God”, although some Protestants prefer to use the term “God-bearer”.[citation needed] Catholics and Protestants agree however, that “Mother of God” is not intended to imply that Mary in any way gave Jesus his Divinity.

Both Catholics and Orthodox, and especially Anglicans, make a clear distinction between such veneration (which is also due to the other saints) and adoration which is due to God alone. (The term worship is used by some theologians to subsume both sacrificial worship and worship of praise, e.g. Orestes Brownson in his book Saint Worship. The word “worship”, while commonly used in place of “adoration” in the modern English vernacular, strictly speaking implies nothing more than the acknowledgement of “worth-ship” or worthiness, and thus means no more than the giving of honor where honor is due [e.g. the use of “Your Worship” as a form of address to judges in certain English legal traditions]. “Worship” has never been used in this sense in Catholic literature when referring to the veneration of the Blessed Virgin). Mary, they point out, is not divine, and has only such powers to help as are granted to her by God in response to her prayers. Such miracles as may occur through Mary’s intercession are ultimately the result of God’s love and omnipotence. Traditionally, Catholic theologians have distinguished three forms of honor: latria, due only to God, and usually translated by the English word adoration; hyperdulia, accorded only to the Blessed Virgin Mary, usually translated simply as veneration; and dulia, accorded to the rest of the saints, also usually translated as veneration. The Orthodox distinguish between worship and veneration but do not use the “hyper”-veneration terminology when speaking of the Theotokos. Protestants tend to consider “dulia” too similar to “latria”.

Our Lady of Vladimir, one of the holiest medieval representations of the Virgin.

The surge in the veneration of Mary in the High Middle Ages owes some of its initial impetus to Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard expanded upon Anselm of Canterbury‘s role in transmuting the sacramental ritual Christianity of the Early Middle Ages into a new, more personally held faith, with the life of Christ as a model and a new emphasis on the Virgin Mary. In opposition to the rationalist approach to divine understanding that the schoolmen adopted, Bernard preached an immediate faith, in which the intercessor was the Virgin Mary. “the Virgin that is the royal way, by which the Savior comes to us.” “Bernard played the leading role in the development of the Virgin cult, which is one of the most important manifestations of the popular piety of the twelfth century. In early medieval thought the Virgin Mary had played a minor role, and it was only with the rise of emotional Christianity in the eleventh century that she became the prime intercessor for humanity with the deity.” (Cantor 1993 p 341)

Some early Protestants venerated and honored Mary. Martin Luther said Mary is “the highest woman,” that “we can never honour her enough,” that “the veneration of Mary is inscribed in the very depths of the human heart,” and that Christians should “wish that everyone know and respect her.” John Calvin said, “It cannot be denied that God in choosing and destining Mary to be the Mother of his Son, granted her the highest honor.” Zwingli said, “I esteem immensely the Mother of God,” and, “The more the honor and love of Christ increases among men, so much the esteem and honor given to Mary should grow.” Thus the idea of respect and high honour was not rejected by the first Protestants; but, they came to criticize the Catholics for blurring the line, between high admiration of the grace of God wherever it is seen in a human being, and religious service given to another creature. The Catholic practice of celebrating saints’ days and making intercessory requests addressed especially to Mary and other departed saints they considered (and consider) to be idolatry. With the exception of some portions of the Anglican Communion, Protestantism usually follows the reformers in rejecting the practice of directly addressing Mary and other saints in prayers of admiration or petition, as part of their religious worship of God. Protestants will not typically call the respect or honor that they may have for Mary veneration because of the special religious significance that this term has in the Catholic practice.

Today’s Protestants acknowledge that Mary is “blessed among women” (Luke 1:42) but they do not agree that Mary is to be venerated. She is considered to be an outstanding example of a life dedicated to God. Indeed the word that she uses to describe herself in Luke 1:38 (usually translated as “bond-servant” or “slave”)[36] refers to someone whose will is consumed by the will of another – in this case Mary’s will is consumed by God’s. Rather than granting Mary any kind of “dulia”, Protestants note that her role in Scripture seems to diminish – after the birth of Jesus she is hardly mentioned. From this it may be said that her attitude paralleled that of John the Baptist who said “He must become greater; I must become less” (John 3:30)